Biography: The Early Years

John Basmajian was born September 23, 1899, in Jersey City, New Jersey of Armenian parentage. His father and mother came to America in 1895 around the beginning of the Hamidian or Turkish–Armenian massacres. They did not know each other until they met in America and later married. The father, Thomas Basma(d)jian, was from Dikranagerd, City of Dikran, a walled city in old Armenia which was part of the Ottoman Empire. Today, it is known as Diyarbakir and is in modern Turkey.

Thomas (Tumas) came from a long line of silk printers who used carved wooden blocks to make the designs. Of the seven brothers of the Basmajian family in Armenia, only John’s father and one other brother came to the New World. Another brother went to Lebanon. The rest are unaccounted for, so there is no further record of what happened to any other family members who may have survived.

After spending some years as a foreman in one of the silk mills located on the east coast, either Massachusetts or New Jersey, John’s father decided to open a tailor shop. The family lived upstairs over the shop at 503 Palisades Avenue in Jersey City. Before John (Johnny to those who knew him) Basmajian was ten years old, he was already helping in the shop, learning to clean and press along with a number of other rudimentary steps in tailoring.

Johnny had two younger brothers, Eddie and Leo, and his father kept a tight reign on the boys. Johnny’s mother disciplined them simply by pinching them on the arm very hard which, as it turned out, was a greater punishment to the boys than the rod. Johnny, when remembering his mother, who died when he was eighteen, always spoke of her as “a real honey, the kindest and nicest mother anybody could have.”

Of these youthful days Johnny further recalled, “I was working for Osgood during vacation through the school years. It was an advertising firm in New York [City]. They were doing fashions. In the old days, they didn’t have color photography, see? They had to paint the fashions. Osgood supplied the pictures, which were done by their illustration artists. They actually put the serge [a silky fabric so woven as to have the appearance of parallel diagonal lines or ribs over the surface of the cloth] in the suits, just those lines in the serge…the artist did all that!”

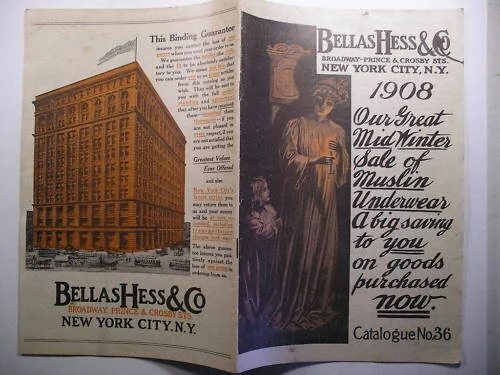

“So I was working for them as a runner. Runners used to take an artist’s drawing(s) to the client for an okay. I used to take these to the various catalogue people like Bellas Hess. In them days, it was Bellas Hess. I don’t remember Montgomery Ward or Sears… it was Bellas Hess. Bellas Hess used to okay the drawing and when the drawing went back, it went to the printer for the catalogue.”

The artists who worked for Osgood’s took an interest in Johnny. They were helpful to him in correcting his drawings and making suggestions for improvement. The wash artists showed him how to put on the watercolor wash and the technique of drawing garment textures. Johnny was about fourteen at that time, and it was at Osgood’s that he learned the techniques to make silk look like silk and serge look like serge. He also mastered the detailing work of buckles, buttons, laces and other trimmings for the fashions of the day.

While still a teenager, Johnny worked in the shipyards during the last years of World War I. He caught hot rivets. The war ended before he came up for the draft.

Overall, he received a very good education from the artists at Osgood’s who took him in tow and taught him through experience. The Art Student’s League further formalized and advanced his training and talent.

“I was just a plain little rascal,” Johnny once reminisced to his granddaughter. “I played hooky many times from school. We guys would go down to the docks to go swimming in the Hudson River. The first time I jumped, I didn’t know how to swim, but I was dared to jump and I did. Then I paddled for dear life, dog fashion, to a small square wooden raft of some kind.” This scary experience did not stop young Johnny from repeating himself. “I got better each time I jumped,” he would say.

Before and after this time of rivet catching, Johnny was attending art school at night, helping his father at the tailor shop after school and finding time for a bit of fun. He often went around “hawking” (renting) seat cushions at open-air concerts or movie showings during the summer at five cents a cushion. “That way we got to see the programs, too.” Many of the early films were being made in Englewood, New Jersey, at the time and Johnny would be an interested bystander whenever he found a movie being filmed on the streets.

It was about this time that Johnny started going to the Art Student’s League in New York. He was particularly impressed with the Gibson Girl artwork and decided to go in for clothing design.

The Art Student’s League taught many of the well known artists at that time, Norman Rockwell included. Johnny greatly admired N.C. Wyeth, Howard Pyle and J.C. Leyendecker. To study their work, he used to stand in front of department store windows displaying their ad illustrations. He was particularly fascinated by J.C. Leyendecker because of his style, which differed from that of his contemporaries, especially his illustrations for the Arrow Collar ads. “The lines of Leyendecker fascinated me,” Johnny would often remark.